So the summer holidays came. As usual I was not looking forward to them. Rob was out of circulation, staying with relatives in Dorset. But quite early one morning, after a fortnight of boredom, I had a phone call out of the blue. To my surprise it was Alex, in a state of obvious excitement.

"Sam! We've found something that looks important! Can you come over and have a dekko? Stay with us, for as long as it takes. Hugo's here too."

He refused to give any details. But it was a godsend. I browbeat my parents into granting me leave of absence, and leapt on a train. By two I was at Andover, being met by a battered Volvo -- nice to find another family whose car was as battered as ours -- by Alex, by Hugo, and by Alex's mum who insisted on being called Charlotte and proved delightfully easy-going. In reply to my fevered questions they all gave a maddening 'wait and see!' After a few miles on the Salisbury road we turned off to meander along the lanes through Nether Wallop -- an archetypal English village of thatched cottages set in archetypal rolling English countryside -- and the despised Bishop's Bumley, until we turned in to Bumley Grange. It was a large and rambling place, its brick and tiles a mellow red, its tall chimneys blatantly Tudor, and it had a run-down look.

"There used to be masses of land," Alex said as we drove up. "William Stevenson's dad was stinking rich. And William inherited the whole estate, plus enough dosh to found Hambledon. But most of it's been sold off to pay for this and that, and now we're down to three acres."

Without ceremony the boys rushed me indoors and into the hall. I don't mean the entrance hall, but The Hall, the main room of any substantial Tudor house. And God, what a room! Huge, high, its ceiling ornamentally plastered, its walls panelled in oak and hung with portraits. In the middle of one side was a vast fireplace. It being August, there was of course no fire in it, though to heat this cavern in winter they'd need a monster. None the less the place felt warm and welcoming. By a window was a table at which they sat me down. Beside the table was a large and dusty carved chest. On the table was a sheaf of paper -- thick firm paper -- covered in brown writing. The hair rose on the back of my neck.

"We found the chest up in the attic, and this was in the chest. We can't make head or tail of it. But we're hoping against hope . . ."

We have it easy, these days. We write everything on PCs. We read Shakespeare & Co in neatly-printed texts, usually modernised in spelling and punctuation. Tudor handwriting is another matter. In my limited experience it varies from the painful to the impossible. Court hand isn't too bad, the style they used for formal things like legal documents, written nice and regularly on vellum. I'd managed a few lines of Hambledon's charter of 1559 which hung framed in the library there. Ordinary day-to-day scribblings with a dodgy quill are a different kettle of fish. Experts, of course, can read the stuff like yesterday's newspaper, but while I knew I was a geek it was why they'd whistled me up -- I knew there were limits to my geekiness. But I had to try. And there was something indefinable in the atmosphere that was urging me to try.

This guy's writing seemed to fall into the impossible category. At first glance I couldn't make head or tail of it either. The layout of the top sheet certainly looked like a play, with lines of irregular length. But it didn't look like the first page. Ah!In the top corner was a faint number 5. I scrabbled through the pile. Yes, the sheets were well and truly out of order. Forcing myself to be calm, I leafed through them until, near the end, I came to what obviously was the first page.

As you may have noticed, I'm not much given to using the f-word. Not because I'm a prude, but because it seems to me to reflect poverty of language. Instead, on this occasion, I recall bellowing, "Bugger me backwards!"

I was on cloud nine, high above the earth. Alex and Hugo were down below shouting "What? What?"

I returned to earth enough to read the words to them, pointing to each in turn.

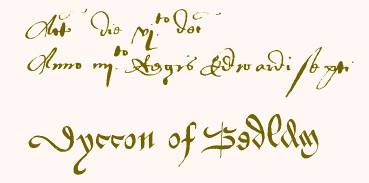

"Acted the sixth day of December in the fourth year of King Edward VI. Dyccon of Bedlam."

They both uttered the f-word, loudly. Charlotte, drawn by the din, came in and had to be told too.

"Well, tickle my pitcher!" she shrieked. I wasn't quite sure what she meant, but subsequent research confirmed my suspicion.

"The sixth of December!" Hugo exclaimed. "That's the same day as our show! And what's the fourth year of Edward VI?"

I counted on my fingers. "1550."

"And why's that bit in Latin?"

"Added by a college official, I'd guess. A note that it had been accepted and performed."

"And it really is Gammer, is it?" he asked anxiously. "Just with the other title?"

I was now like a cryptographer with the key to the code. Below the title the page launched straight into the text, with no list of characters. And because in our production the prologue was being spoken by Diccon, I had it by heart. As I slowly repeated it, the scribbles on the page began to fall into place. Old spellings, a minimum of punctuation, but they were the same. I had cracked the code.

As Gamer Gurton, with manye a wide stytche

Sat pesynge & patching of Hodg her mans briche

By chance or misfortune as shee her geare tost

In Hodge lether bryches her needle she lost.

"Yes,thank God," I said, in huge relief. "It's Gammerall right. Now . . . the first thing is to get the pages in order. Then I'll have to go through the lot to see if there are any major differences. But it's going to be a slow job, till I get my eye in."

So we sorted the sheets according to their numbers, forty of them, written on both sides. From time to time we noticed that single words had been crossed out and replaced by others.

"Look at this!" said Alex suddenly. "There are whole lines crossed out here. One, two, three . . . nine of them. Oh no, eight -- I think one's split between two characters."

A fewsheets on, Hugo found a further pair of lines crossed out. But that was all.

"Well, let's start with Hugo's bit," I suggested. "It's shorter." I got out my printed edition of Gammerin case it would help, and glared at the lines on either side of the crossing-out, trying to get an idea of whereabouts we were in the play.

Capital letters stood out from the rest, and there were five words in a row starting with capitals –H, K, C, T, S. The H surely belonged to Hodge. In the whole play I recalled only one capital K. Bingo! It was about Hodge's date with Kirstian -- 'Hodge:Kirstian Clack Tom Simsons maid.' Yes, and the next two lines fitted. Then came the two crossed-out lines. I wrestled with the wretched scrawl, comparing unknown letters and letter combinations with those I knew, and it took me half an hour to be sure of those two lines. And wow! What lines! I looked across at Hugo and Alex, bored by now and sitting on the sofa, heads together, chatting. Charlotte had long since disappeared somewhere.

"They're your lines, Hugo," I said. "Act II Scene 1. They're about your relationship with Alex. This is what you say, unexpurgated." (I give it here in modern spelling, the new lines in bold).

"Hodge. Kirstian Clack, Tom Simson's maid, by the mass, comes hither tomorrow.

I'm not able to say, between us what may hap.

She smiled on me last Sunday, when I put off my cap.

These five years past has been my sport to tumble Cock our boy,

But now I feel a pricking need to fill a maid with joy.

They looked at each other and burst into hoots of laughter.

"Watch it, Hugo!" said Alex. "You keep clear of Kirstian, or else!"

"Wouldn't touch her with a bargepole," Hugo replied. "OK, Sam. So now you know about us. We're in love." My suspicions were confirmed. "That's why I'm here. Not for this manuscript. We only found it last night. But I've been here since the end of term."

"These two weeks past has been your sport to tumble Cock your boy?" I suggested slyly.

"I wish," Hugo said, squeezing him. "God, I wish." He swallowed whatever he was about to say. "I don't call him Cock, though. I did try calling him Hernia, like Lysander did in the Dream."

"Bit rude that, wasn't it?"

"No ruder than calling him Cock. But when I started saying 'Oh joy, oh rupture!' he objected."

Alex punched him. "And I wish too. Mum knows we're in love. She's very laid back about it. But she does draw the line at tumbling. Even at us sleeping in the same room. Still, it's less than a year till I'm sixteen. Age of consent. I think she'll say yes then."

I marvelled at the love and trust that made him obey her. I wouldn't have obeyed my parents, not in these circumstances. "Roll on the day, then." I said in sympathy. "OK, I'll go back to the earlier lines. But they're likely to take even longer. A couple of hours, maybe."

It was now five. "That's all right," Alex said. "We'll be eating about seven."

"But can I use a computer? I may need to look things up online, and I'd like to type this up."

"Sure. I'll bring my laptop down."

He plugged it in and, not being able to help, they went next door to watch cricket on the telly.

Although alone, I still had the odd feeling of a benign presence and, as my eye grew attuned to the idiosyncracies of William Stevenson's handwriting, the job became easier. It was not much more than an hour before I was satisfied with the result. And it proved to be both a confirmation and a puzzlement. I typed it up, added what seemed to be appropriate stage directions, and went next door. Hugo and Alex were canoodling in front of the cricket, and I dragged them to the hall.

"Here you go," I said, pointing to the screen. "Act I Scene 4."

Cock[within]. I cannot get the candle light -- here is almost no fire.

Hodge.I'll hold thee a penny I'll make ye come if that I may catch thine ears!

Art deaf, thou whoreson boy? Cock, I say! Why, canst thou not hear us?

Cock.Tush, Hodge, I hear thee. I but move the inglecock

To blow the fire up.

[Noise within]

Hodge. By the mass! What the devil's that knock?

Cock. God's bones! Deep am I spitted! O that it should come to pass!

I backward fell, and the inglecock hath pricked me in mine arse.

[Emerges impaled by the inglecock]

Hodge. Thou cox! Thou whoreson ingle! Into thy shitten bum

Am I not the only neighbour whom thou allowest to come?

Stay still! I'll draw this varlet cock forth from my Cock's breech,

[Pulls it out]

Andto admit no trespass more, so I shall him teach.

[Spanks himlustily]

Gammer. Beat him not, Hodge, but help the boy, and come you two together.

"Wow!" they cried as they read it.

"Nice, isn't it?" I said. "I always thought there was more to those comings than meets the eye. But what the hell is an inglecock?"

They shrugged their shoulders.

"It sounds like a sort of bellows," said Alex. "But how do I get it up my arse? What is an ingle, anyway? Thou cox, thou whoreson ingle-- what does that mean?"

"Coxis a fool. Whoreson's a term of abuse, son of a whore, like us calling someone a bastard without meaning it literally. Inglemeans two things." I clicked the screen to bring up the online Oxford English Dictionarywhich was lurking behind my script."It can be a fire in the hearth. Hence inglenook, an alcove for the hearth, and presumably inglecocktoo, a cock for the hearth, whatever that means. And look -- inglecan also be 'a boy favourite (in bad sense), a catamite.'"

"What's a catamite?"

I typed it in. 'A boy,' the dictionary told us, 'kept for unnatural purposes.'

Alex was cross. "Itisn'tunnatural."

"Of course it isn't. That's just the OEDbeing old-fashioned. Anyway, your revered ancestor's got two plays on words here. There's inglethe hearth and inglethe boyfriend. And there's coxthe fool and Cockthe boy and cockthe prick and cockthe something else. Cockmeans all sorts of things." I typed it in. "Here you are. Noun 1, sense 20, a penis. Deriv

ed from sense 12, a short pipe or spout or nozzle -- it doesn't necessarily have a tap to turn it off, like a stopcock does. Which makes sense. After all, a penis is essentially a short pipe or nozzle or spout, isn't it?"

Alex was giggling. "And once it starts spouting you can't turn it off. Though I haveseen one pipe that isn't exactly short." He put his hand on Hugo's crotch.

"The problem," I persisted in the face of this levity, "only arises when ingleand cockcome together."

"It isn't a problem at all," Alex said, now giggling fit to bust. "The cock arises automatically when it meets the ingle. And once they've come together you can't do much to stop it coming."

"Even when the ingle has a shitten bum?" Hugo was almost pissing himself with laughter too.

"And Hugo!" Alex's voice reverted to a squeak. "You've got to spankme!"

"Lustily. That means spank you hard!"They giggled on, until at last Hugo returned to the point. "Sorry, Sam. Let's get back to the inglecock. We still haven't got to the bottom of it."

Which of course sent them off again.

"Cock," I went on when the meeting was finally restored to order, "is trying to revive the fire. And therefore he tries to move the inglecock. But he falls backwards and knocks it over, which makes quite a shindig. And it pricks him in the arse. Impales him like meat on a spit. Hodge has to pull the thing out. So an inglecock must have some sort of spout or nozzle like a bellows does. But if you fall backwards onto a bellows it'll hardly find its way into your arse. And inglecockisn't in the OED, and there's nothing relevant on Google. I'm floored."

So were they. We printed out the new additions to the text, and we had to adjourn the meeting when Charlotte called us in to dinner. It was a great meal. Not just the food, but the atmosphere. She enquired, of course, about our progress, and Alex unconcernedly showed her the print-out. I couldn't imagine showing such a thing to my own parents. And, where my parents would have gone through the ceiling, she didn't turn a hair.

"It's uncanny, isn't it," she said, "that you two should be cast, all unknowing, as Hodge and Cock, and should fall for each other. And here's William prophesying it, almost. Giving you his blessing, in a way."

"Well, I know he approves," said Alex. "Don't you, William?" he asked into thin air.

Honest truth, I swear I sensed a message of agreement from somewhere. Wondering if I'd actually heard it, I looked round. Charlotte laughed. "You won't see him, Sam. Nobody ever has. But -- I know it sounds daft -- we often sense that he's around. He's not in the least eerie, just a comfortable presence. He's not so obvious to me. Maybe it's because I'm not a Stevenson by birth, or I'm the wrong gender. But he was obvious to Alex's dad, and to his father. And he's obvious to Alex."

He was obvious to me too. I don't think I'm unduly credulous, and I'm certainly not into ESP, but it was hard to deny what my senses told me. What a wonderful presence to have in the house.

"He lived here, you know," said Alex. "He was born up north, but when his dad built this place the family came down, and William grew up here. His parents died when he was about fourteen, so from then on it was all his. He lived here too when he had to leave Cambridge under Mary. But soon after that he moved up to Durham and married. It wasn't long before he died, though -- he was only in his forties -- and his wife and son came back here. We've been here ever since. And that chest in the attic's probably been here ever since."

"What else is in the chest?"

"We haven't looked properly. All we've seen is masses of legal-looking stuff. Someone'll have to plough through it, once we've sorted out Gammer. Once you've sorted her out."

As the meal progressed, I learnt a number of things I hadn't heard before. Alex's father and grandfather had both died quite young -- a worrying habit of the Stevensons, it seemed -- before there was any chance of passing on family lore to their sons. That was why nobody living had any idea of what might be in the attic. And once her husband was gone, all of Charlotte's energies were spent on bringing up Alex single-handedly and on making ends meet. She was a professional potter -- and, I gathered, a highly successful one who exhibited all over the place -- with her studio in one of the barns. Even so it was pretty clear, though she did not say so, that finances were tight. Giving a youngster as normal a lifestyle as possible and paying his fees at Hambledon, not to mention the prospect of university, does not come cheap. I knew that well. My parents had often told me so. On top of that was the surely phenomenal cost of keeping a place like Bumley Grange going.

She excused herself to return to her pots, while we did the washing up. Then Alex showed me my room.

"It used to be the main bedroom," he explained. "But when Dad died, Mum felt she was rattling around in it, it's so big, and she moved to a smaller one. So now it's just a guest room."

Big it was. And its crowning glory was a great four-poster bed, complete with curtains.

"I'm sure William slept in that," Alex said. "I slept here last holidays when my room was being patched up, and he was in it too. He wasn't at all, um, off-putting. I mean, he didn't mind me having a wank. In fact he seemed to approve."

"Even though he was a reverend!" Hugo marvelled.

"Not all reverends are stuffy," Alex pointed out. "Look at Crack." He was the school chaplain. "Anyway, the William who's around here isn't old and stuffy. He's quite young, about our age. And he thinks like us. I'm sure of that."

The omens were good. But it was far too early to put them to the test, and the damned inglecock was still niggling me. I decided to go back to the laptop, and they sloped off to watch a Prom on the telly. The answer, I told myself, must be somewhere on the web. The problem, as usual, was how to find it. Google was useless on inglecocks. But what about searching under their function? The things were for blowing a fire, so I tried 'fire-blower.' Over four million hits, all of which -- or at least the first hundred -- were either about modern machines or about people who eat fire. Forget it. What about 'hearth-blower'? Better, only 32,000 hits. I scrolled down the first page.

And there it was, or what might well be it.I clicked on it.

Cambridge University Press was announcing the contents of the Antiquaries Journalfor 2007 which included an article on 'Jack of Hilton and the history of the hearth-blower.' It proved to be one of those maddening academic sites where you have to pay for what you want. But at least it gave a short abstract, which read:

'The resurfacing of a late medieval hearth-blower for fanning the flames of a fire provides the opportunity for a review of the type. Examples of these anthropomorphic aeolipiles from England, all late medieval in date, are placed in context, both in time -- stretching back to the Classical period -- and in space.'

Uh? Anthropomorphic aeolipiles? AnthropomorphicI could do -- in the shape of a man -- but for aeolipileI had to return to the OED. 'A pneumatic instrument or toy,' it said, 'illustrating the force with which vapour generated by heat in a closed vessel rushes out by a narrow aperture.'

Warmer, definitely warmer. But just how did it work? What did it look like, apart from a man? Well, there was still 'Jack of Hilton' to Google. I typed it in. Only 36 hits. One of them was an old book.

'At Hilton, Staffordshire,' it said, 'there existed a hollow brass image representing a man kneeling in an indecorous position known as the Jack of Hilton. The image had two apertures, one very small at the mouth, another larger at the back. When filled with water and put to a strong fire, the water evaporated as in aeolipile, and vented a constant blast from the mouth, blowing audibly, and making a sensible impression on the fire.'

I was beginning to understand the principle. And indecorous? That was even more interesting.

Another item, better still, was a report of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford which had recently acquired Jack of Hilton himself. It described him as a 'hollow-cast copper alloy figure, 31 cm high, late 13th or 14th century. A rare example of an aeolipile: the vessel was filled with water and warmed on the hearth to fan the flames with a jet of air released through the steam–pressure created within.'

And alongside the description was a photo which showed just how indecorous he was.

Eureka!

I ran next door and shouted to Hugo and Alex, who came bounding in.

"There you go!" I crowed. "There's our inglecock! This one's called Jack of Hilton."

They goggled. "Well, he's having a nice wank!" Hugo observed. "And look at those lovely balls! But I'm not with it. Does the air come out of his cock?"

"No. Out of his mouth."

"But if he's full of water," Alex pointed out practically, "it wouldn't be air. It would be steam. And wouldn't that put the fire out?"

To that I had no answer.

"And look!" Hugo added, reading the description. "He's a midget. He's only a foot tall. So his cock can't be more than a couple of inches long. When Cock gets impaled, it would hardly go in!"

"Maybe there were bigger inglecocks."

"He's not the only one, then?"

I showed them the abstract on the CUP site. "Looks like there are quite a number," I said. "We've got to get hold of this article. But how many libraries have the Antiquaries Journal?Where's the nearest decent one?"

"Bugger libraries!" cried Hugo. "You can buy it online. Look, it says so!"

"Yes, but it costs twenty quid."

"No prob." I'd been forgetting that he, or his parents, were well heeled.

He fished out his credit card and got busy. Within five minutes we had the article on screen and printed it off. It was highly informative. There were examples, though not anthropomorphic ("what does that mean?" asked Alex), from as far east as the Himalayas. From Europe nine anthropomorphic examples were known, of which three were of Roman date, three were medieval from the continent, and three were medieval from England. Like Jack, several had hard-ons, though none of the others was wanking. Most stood -- or knelt -- no taller than Jack. But one was 57 cm high.

"Almost two feet," said Hugo. "That's better."

The article also explained the workings better. Fill the thing with water via a hole at the back of the head. Put a bung in the hole. Sit it in the embers until it boils. And the jet of steam coming out of the mouth entrains air with it, which blows up the fire.

"Why," Hugo wanted to know, "can't the steam come out of its cock instead?"

"Too low down," Alex explained. "It's under water. But maybe you're supposed to think it's the cock doing the work. Wanking into the fire."

These things weren't mentioned in contemporary literature, the article implied, and no contemporary name for them was known. We sat down on the big sofa to chew that over. Perhaps the name had simply gone unrecorded, except in Gammer. And what about the dates? None of the things was later than the fourteenth century. But Gammerwas two centuries after that, give or take.

"William must have seen one, though," I mused. "Can they have had one at Christ's? In the hall? No, probably not. Too risqué. But I wonder if there was one in his family, and it had come down as an heirloom. These things can't have been cheap. You say the Stevensons were well off, Alex, even before they came here?"

"Oh yes. They had masses of land up in County Durham, round Bishop Auckland."

"But if inglecocks weren't cheap," Hugo objected, "what's one doing in Gammer's house? She's not much more than a peasant. She only owns one needle."

"Gammer's fiction, remember. A frivolity, miles away from real life. Anything to bring in a bit of fun. I still think William had seen one. Maybe even had one. And so he put it in his play . . ."

All three of us felt that warm young presence again. We looked at each other, and then at the fireplace. Its floor was of old brick laid in a herringbone pattern, on which stood a large basket grate that was clearly fairly modern, a pile of logs, a bucket of kindling, and a number of pokers and tongs. In that respect, an ordinary fireplace. But it was very big, and very old.

I was the first to put thoughts into words. "He was about seventeen. He'd invited a few of his mates from Christ's to spend Christmas here. Maybe they tumbled each other, who knows? Anyway, they were sitting round this fire, well-fed, well-wined, giggling at the inglecock, making rude jokes just like we do. They'd seen a play or two at Christ's and been bored by them -- too decorous, or too nonsensical. William announced that he was going to write one himself. One that would be more fun. They threw out ideas, and he noted them down. And one of those ideas was to bring in the inglecock, which was sitting in front of them and wanking into the fire. Something like that."

We sat there, visualising it. "Yes," they said. "Something like that."

We sat on, thinking. The room was rather different now, in August, not yet fully dark. Charlotte came in to offer us a hot drink. We turned it down, but put her in the picture. She studied Jack with interest, and laughed heartily. And her eyes too turned to the fireplace.

"You know," said Hugo suddenly, "we've gotto have an inglecock in the play, to impale Cock. But we can't just go into a shop and buy one. We'll have to get one made."

Welooked at each other again, and simultaneously we shouted "Rob!"

"Mum," said Alex. "Can Rob stay here, if we can get him?"

"Of course."

"D'you know where he is, Sam?"

"In Dorset, I think, though he'll be going home soon. I'll see if I can raise him."

I got busy on my mobile, and Rob answered at once. "Sam! Nice to hear your cheerful voice! Where are you? What are you up to?"

"I'm at Alex's, near Andover. Hugo's here too. What we're up to . . . well, it's totally brilliant. Gammerstuff. Much too complicated to explain now. The point is, we need you. Urgently. You're still in Dorset? And going home when? Tomorrow!"

"As ever is. And if you're near Andover, it's easy as falling off a bog. My train goes through Andover, so I can jump out there rather than carry on to London. I'll square it with my parents. Can I stay at Alex's?"

"Of course."

"And how do I get there from Andover?"

"Hold on." A quick word with Charlotte. "We'll meet you at the station."

"Great. I'll find the exact time and text you. Till then!"

Alex and Hugo scuttled back to the tellyto catch the end of their Prom, and Charlotte announced that she'd get a room ready for Rob.

"Oh, please!" I cried, alarmed. "Can't he sleep in my bed?"

She gave me an unfathomable look. "Is that to save me the trouble of making up another? Or -- how do I put it delicately? -- is he your boyfriend?"

No doubt I blushed. "Yes. But boyfriendsounds so, um, temporary. I'd rather call him my partner."

She caught all the implications. "That sounds good and permanent."

"Yes. It's not just a trial. We fit. We're going to stay together."

"Then by all means sleep together. . . And in that case, Sam, may I ask your advice?"

"Of course." What the heck did she want myadvice about?

"And what about a dram of Scotch? I don't often have one, but I need it today, and after all your labours I expect you do."

"Thanks." Rob had introduced me to Scotch at his home, and I had taken to it.

She poured it, and we sat down on the sofa.

"Sam, you know that I've put my foot down about Alex and Hugo sleeping together?" I nodded. "Well, I like to think I'm broad-minded. I find Gammer's humour as funny as you do. I adore your inglecock. And I've nothing whatever against being gay. It's the way you're made. So if Alex is in love I can't slap down on him. Where I havedrawn the line is sex, at least till he hits the age of consent. And that's because I know so little about Hugo. All right, he's a personable and intelligent lad, and he comes across in a good light. But what's he after? Love, or just sex? It's an important distinction, isn't it? Can you fill me in?"

I could, gladly. "His family's rolling, and in that sense I think he's a bit spoiled. But he isn't spoiled in the bigger sense. He's a great bloke. Time was when he was stand-offish. But now, if he's with people on an equal footing, he's considerate and he's generous. He's learnt it the hard way. He had an affair with another boy, but Edward was possessive and selfish and was after nothing but sex, and even that was all one-sided. Then six months ago Hugo had the sense to drop him, and since then he's been fine. Of course he wants sex -- who doesn't, at our age? -- but he wants much more than that. Look, put it this way. Rob's the best. But if I'd never met Rob, I'd happily live with Hugo. And I'm sure Alex will too. I can't see any Kirstian putting a spanner in the works."

"Thank you, Sam. That's a good testimonial. You're seventeen, aren't you?" I nodded again. "A year older than Hugo, two years older than Alex. Before you arrived they were singing your praises. Not because you're gay. They didn't mention that, and I wasn't aware of it till just now. But they're right. You arecompetent and perceptive and responsible. Not that they used those words."

Me? All of those? Well, Rob and I were going to be prefects next term, when we'd have to keep our noses reasonably clean. In other words be fairly responsible. Even so . . . I made a deprecatory noise.

"Oh, come off it, Sam! Look at your researches into Gammer-- that's competence. Look at what you've just told me -- that's perceptiveness. Look at producing a school play from scratch at sixteen -- that's responsibility . . . So you think they're responsible enough? That it wouldn't do any harm if I lifted the ban on sex?"

"I think," I replied simply, "it would be good for them. Both of them. Because I know how good Rob's been for me."

"All right," Charlotte said. "I'm persuaded. I'll lift the ban. It's great, you know, that you've all sussed out your sexuality so young. Leave it too late, and you're liable to get hang-ups about it."

Clinking glasses, we drained our Scotch, and she called Alex and Hugo in from next door.

"Boys, Sam and I have been having a chat. And so long as you're clean and considerate, you're now free to sleep together."

It isn't often that you see mouths literally drop open in astonishment. Alex gave his mum a great hug, and Hugo -- to myastonishment -- gave me one too. Then they swapped over. Then they disappeared eagerly to bed. I bade Charlotte good night and went up more sedately, thinking that I'd done my good deed for the day. Several good deeds, in fact, for surely Gammerand the inglecock counted too. William was there in my room. Whether he was off-putting I had no idea, because I dropped straight off in his four-poster without even contemplating any activity.

Authors deserve your feedback. It's the only payment they get. If you go to the top of the page you will find the author's name. Click that and you can email the author easily.* Please take a few moments, if you liked the story, to say so.

[For those who use webmail, or whose regular email client opens when they want to use webmail instead: Please right click the author's name. A menu will open in which you can copy the email address (it goes directly to your clipboard without having the courtesy of mentioning that to you) to paste into your webmail system (Hotmail, Gmail, Yahoo etc). Each browser is subtly different, each Webmail system is different, or we'd give fuller instructions here. We trust you to know how to use your own system. Note: If the email address pastes or arrives with %40 in the middle, replace that weird set of characters with an @ sign.]

* Some browsers may require a right click instead

Most of it was covered with the usual scrawl, but at the top were two short lines of better writing. They were in Latin, and I could just about read them. Below them, in different and still better writing, was the title, in English. I could read that too. Easily.

Most of it was covered with the usual scrawl, but at the top were two short lines of better writing. They were in Latin, and I could just about read them. Below them, in different and still better writing, was the title, in English. I could read that too. Easily.