Note

Although this story is set in Wales, the Welsh language plays little part in it. For those who like to pronounce the more important names aright, Cilmin is (fairly obviously) Kilmin, Clynnog is Klunnog, and Lleuar approximates to Hlay‑ar, all with the accent on the first syllable. For further guidance, see http://www.cs.brown.edu/fun/welsh/Lesson01.html.

All verses in the chapter headings and ( limericks apart) all unattributed verses in the text are by Robert Hunter. All the places mentioned are real, although I have moved Lleuar to a new site. All the historical personages mentioned are also real, although Cilmin Droed-ddu, St Beuno and St Cybi are only mistily so. But all the present-day characters are wholly imaginary.

As should be clear enough, the chapters are narrated alternately by the two protagonists.

This story is dedicated, with respect and gratitude, to Ben.

July 2005

Not Understood

Not understood. We move along asunder;

Our paths grow wider as the seasons creep

Along the years; we marvel and we wonder

Why life is life. And then we fall asleep --

Not understood.

Not understood. We gather false impressions,

And hug them closer as the years go by,

Till virtues often seem to us transgressions;

And thus men rise and fall, and live and die --

Not understood.

Not understood. Poor souls with stunted vision

Oft measure giants by their narrow gauge.

The poisoned shafts of falsehood and derision

Are oft impelled 'gainst those who mould the age --

Not understood.

Not understood. The secret springs of action

Which lie beneath the surface and the show

Are disregarded; with self-satisfaction

We judge our neighbour, and they often go --

Not understood.

Not understood. How trifles often change us!

The thoughtless sentence or the fancied slight

Destroys long years of friendship, and estrange us,

And on our souls there falls a freezing blight --

Not understood.

Not understood. How many breasts are aching

For lack of sympathy! Ah day to day

How many cheerless, lonely hearts are breaking!

How many noble spirits pass away --

Not understood.

O God! that men would see a little clearer,

Or judge less harshly when they cannot see;

O God! that men would draw a little nearer

To one another; they'd be nearer thee --

And understood.

Thomas Bracken

1. Cilmin

Walk into splintered sunlight,

Inch your way through dead dreams

to another land.

Maybe you're tired and broken,

Your tongue is twisted

with words half spoken

and thoughts unclear.

Box of Rain, 1970

Not understood . A short phrase and sharp, hammering in my head like the opening bar of Beethoven's Fifth. Try it in German, then -- nicht verstanden. Different rhythm, but just as terse. Try French and Latin -- non compris, non comprehensus . Different again, yet still succinct. Now try my mother tongue (is it really my mother tongue?) -- dim wedi cael fy neall. Definitely not pithy. Five words where two should do. The language of heaven, they claim, but still a primitive language. Am I a traitor for thinking so?

But all that is mere word-play. None of it matters. Language is only the wrapper round the parcel. What matters is what's inside. Whatever the language, it's me that's not understood. Me, Cilmin. And it's my fault that I'm not understood. If I don't explain myself, how can I expect to be understood? But how can I explain myself, if I don't know what I am? At Penygroes they thought they knew, and laughed at me. Here at Pwllheli they don't laugh because they know nothing about me. Keep it that way. Head down, Cilmin. Be unsociable. Huddle under your hoodie. People assume it hides a menacing tearaway brooding on aggro. It actually hides a wounded teenager bent on anonymity. And it works. They leave me alone.

I suppose, looking back, that last year was easy. I was fresh to Pwllheli. Nobody knew me, nobody got to know me. The move from Penygroes was a good move. The down side was living in Clynnog -- no free transport from outside the college's catchment, only public service buses. But that's all over now, thank God, now that I'm seventeen at last and can drive Dad's old MG. There's a new down side, though. There always is. All the macho lads suck up to the driver of a snazzy red sports car and enthuse about RPMs and injectors and how fast it accelerates from 0 to 100 and can they have a go? None of which is my scene. Macho lads, what's more, tend to have other interests that I don't share. But I'm unsociable with them and they're taking the hint. This year promises to be more relaxed than last. And I will be equally alone.

Which is what I want, yet what I hate. Aloneness means loneliness. Desperate loneliness. At least it does to me. I'm not a natural loner. And aloneness underlines that swamping sense of non-fulfilment. How can you find fulfilment if you don't interact with people? I used to be quite a popular character. Until eighteen months ago I did interact, and I want to interact again. On top of that, I'm conscious of an outward urge, of a sense of rebellion, of an impatience with the narrow world of Clynnog and Pwllheli, of Gwynedd, of Wales. I want to break free. But I'm trapped in this narrow world. Just as I'm trapped by this walnut-shell of secrecy which I dare not let anyone pry inside.

Keeping that shell closed shuts out any hope of fulfilment, any chance of being understood. If I'm to be understood, I've got to open up, I've got to trust, I've got to make my identity known. But what is my identity? An unknown quantity, to most. A laughing-stock, to some. An object of respect and love, to just three people. But what am I to myself? I'm not sure. Am I ashamed of the contents of that shell? I'm not sure. Would I want to change its contents? I'm not sure. I'm different, and proud of my difference. Aren't I? Aren't I? Yet what sane person wants to be fundamentally different?

So I don't know what I am. Maybe there's someone, somewhere, who can tell me. But to date nobody has. The only people I've opened up to are Mum and Dad and the vicar. They sympathise and they support, but I doubt if they know what I am, any more than I know myself. And they're of a different generation. Of my own age, I've not come across a single soul I feel in the least inclined to trust.

So here I am, reasonably good to look at (as if it matters), reasonably well-off (as if it matters), reasonably intelligent (I ought to make university), reasonably likeable (look at my past record), and pining for companionship and more. Yet what am I doing to find it? Hiding under my hoodie.

Such thoughts regularly chased pell-mell around my head, and they chased around it that Tuesday as I sat in the common room belatedly eating my sandwiches. Sandwiches, because the college canteen's menu is far from inspiring. Belatedly, because my history class ran from 12: 30 to 2: 00 and I don't like eating too early. And, as I nibbled the last bit of apple from the core, this boy passed me. I had seen him around a number of times over the first few weeks of term -- evidently a new student and therefore presumably sixteen. I had overheard him talking to his friends in English with a noticeably Scottish intonation -- evidently an incomer. He was eye-turning, too, his manner one of thoughtful independence, his hair curly and almost auburn, his face square and almost freckly, his eyes blue verging on green. Those eyes met mine as he passed, as eyes do, and in them I seemed to see a sympathetic recognition.

He was heading for the lockers. On the spur of the moment I ventured a step which I had never ventured before. I threw my core in a bin, pulled my hood back off my head, and followed him. I rummaged in my locker, he rummaged in his, and as he rummaged he sang softly to himself. The music was hardly my sort. It was the words that held me transfixed like a butterfly on a pin.

In the attics of my life,

Full of cloudy dreams unreal,

Full of tastes no tongue can know

And lights no eye can see,

When there was no ear to hear

You sang to me.

Shut your eyes and listen

to the colours in your mind?

Except for private vision

you might as well be blind.

Coast across the ruin

with the mudflaps of your soul

Slapping to the rhythm

till it sounds like rock and roll.

Easy Answers, 1994

That Tuesday did not begin well. At an unholy hour I was dragged out of bed by a shrill shriek of "Kenneth!" It was Mum, of course, and all het up. She was off to a meeting in Llandudno, she was already late in leaving, and she needed my help in push-starting the car. Her mood hardly improved when I incautiously reminded her that she had known for a week that the battery was on the way out. Nor was my own mood serene. I liked to launch myself into each new day with a little peaceful exercise, in bed, on my back, with my right hand, and my routine had been interrupted. I returned to bed to resume it, but today's fantasies, as well as the delayed explosion, somehow lacked their usual magic.

Showered and breakfasted, I sat in my room in a disgruntled reverie, trying to come to better terms with a misty late September day. I found myself grappling with the melancholy that had so often washed over me since we moved to Wales, and especially in the last couple of years. It was not so much a melancholy of soul as a melancholy of place: of a place that seemed to live not for the future, nor in the present, but off the past. It was a feeling of transience, not always obvious; but once I had noticed it I tended to notice it everywhere.

I noticed it from my bedroom. One window looked out across the flatlands, here less than half a mile wide, to the ridge of Ralltwen which dropped sheer to the back yards of Tremadog, its cliffs offering foothold only to clumps of heather, the scree slopes at their foot invaded by mature oaks. Towards one end was an abandoned slate quarry, light glinting uncertainly from the tumbled slabs on its waste tip. The window in the adjoining wall faced the precipitous slope of Moel y Gest, gashed horizontally by the shelf that had once been a granite quarry, slashed vertically by the incline that had once taken the stone down to the railway. This quarry was equally dead, the spoil that spilled below it heavily colonised with bracken and rhododendrons.

Within the circuit of the foothills, the nearby scenery of fields, roads, railway and housing -- ours included -- lay below mean sea level, protected from disaster by only a single sluice gate. In the foreseeable future, what with global warming and rising sea levels, the immediate area would be under water again. If one returned in five hundred years, what would one find? An empty expanse, no doubt, of tidal mudflats. Even, most likely, the old farmhouses on the foothills would be derelict. Hill-farming was already a precarious livelihood and few youngsters followed in their fathers' footsteps. All that would survive unchanged was the bones of the mountains. They would long outlast mankind, long after the flesh of human endeavour had been corrupted away. Permanence and transience.

I sighed. I was a two-faced character, and could not help knowing it. Until the last few years I had been childishly cheerful and carefree, joke-cracking, laughter-sharing. I still was, to some extent. But since the onset of GCSEs, since the onset of puberty, since the trauma of that atrocious revelation, more and more of the cheerfulness had been whittled away by new preoccupations.

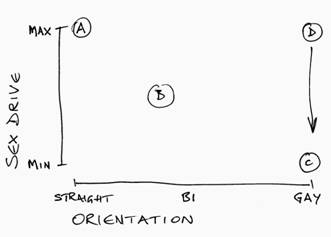

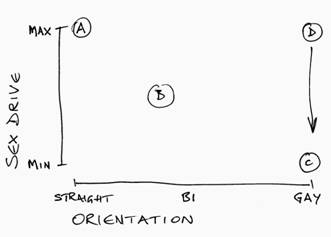

There was my growing workload at school and more recently at college. There were my sexual desires, as insistent as any teenager's but perhaps untypically focussed on gentle and abiding intimacy rather than quick and casual copulations. And, ever-present, there was the responsibility of jollying Mum along and the nagging burden of coping with the flagrant injustices of life. No surprise that the light-heartedness, nowadays, was often overlaid by an introspection which sometimes, like today, took the form of an aimless melancholy.

But it was time to go. I pulled myself together, shovelled my books into my bag, locked up, and walked the quarter mile to the station. One of the many advantages of college over school was that you did not have to be there all day, only for your own classes. If I had an early class, I caught the college bus. If I started later, I took a later train. The reverse when coming home.

And so, this Tuesday, I sat by the grubby carriage window for the twenty minutes it took to trundle the thirteen miles to Pwllheli, ears glued as usual to the headphones of my discman, eyes open to the scenery which was still relatively unfamiliar. Past the same abandoned granite quarry. Over the dreary marsh of Ystumllyn. Beside Criccieth castle, built to subdue unruly Welshmen but, long superfluous in this genteel resort, now a ruin in the care of Welsh Heritage. Past Hafan y M�r caravan park and its incongruously sad jollity. Between the mudbanks of the harbour and the suburban gardens a-flap with washing. Into the diminutive terminus, in every sense the end of the line.

Out of the station, past the cluster of signs pointing to the Promenade, Marina, Toilets, South Beach, Leisure Centre, Library, Golf Course, Aviary. I cackled whenever I saw it. My sense of humour is filthy and I don't mind who knows it, except Mum. And that word aviary always sets me off. Because of a limerick:

There was a young curate called Lavery

Whose desires were uncouth and unsavoury.

With demoniac howls

He deflowered young owls

Which he kept in an underground aviary.

Yes, I know, I know. Think what you like. But I always recited it to myself when I passed that signpost, and today it banished a slice of my melancholy. A couple of hundred yards more, up Stryd Penlan and Troedyrallt, to the college. Coleg Meirion-Dwyfor, to be formal. The Dwyfor campus of it, to be yet more precise, the Meirion campus being in far-off Dolgellau. And down to work.

At least Tuesdays were pleasantly undemanding. Biology class. A quick bite of lunch. Maths class. All over. How easy. Should be able to catch the 2: 37 back to Porthmadog. A cheery word with Megan and Iorwerth. Apart from Mum, Megan was the first person I had come out to. At school I had resolutely kept it under wraps. At college I had decided to be open: not to flaunt it, just to let it be known. I had been there only a week when Megan showed marked signs of interest in me. I liked her, but I had told her straight out that I was not in the running for more than friendship, and why. She had taken it just as I hoped, with no revulsion or contempt, and had drowned her evident sorrow by chasing Iorwerth instead. She had also spread the news, as I told her she could. But there had been no public reaction whatever. Nobody had reviled me. This was a civilised place, it seemed, but also a barren one, for nobody had tried to chat me up either. And Megan was still a good friend. The last of my morning melancholy evaporated like the morning mist.

As I headed through the common room towards the lockers I passed this chap sitting munching an apple. I had seen him around before and, yes, I had already lusted. He was always withdrawn, always alone, always wanting, it seemed, to be alone. He was usually mysterious inside a black hoodie. But when his head was visible he was startlingly attractive. His hair was short and dark, his eyebrows heavy, his mouth expressive, but his brown eyes were sad. And I already approved of him for reasons other than his looks. I had seen him arrive and leave in a cool red MG, which meant he must be seventeen and in his second year. Anyone who drove a cool red MG modestly and quietly, without ostentatious gunning of engine or squealing of tyres, earned my automatic approval.

Today he was wearing his hoodie as normal, hood up as normal. But our eyes met as I passed, as eyes do. In his, shadowed though they were, I saw the usual sadness, but perhaps a spark of hope as well. I sympathised. But contentment was still upon me and, as I scrabbled in my locker, I sang a song to myself. On reaching the end of the first verse I sensed a presence behind me, and swung round. It was the lonely laddie, his hood now off.

"Sorry to eavesdrop," he said, in a voice low in pitch and low in volume. "I was trying to hear. That sounded good."

"My singing? Good?" I laughed. "I've been told my voice is like a bullfrog with the trots."

He smiled back, and the sadness was no longer there. "It wasn't so much the music. It was the words. Where's it from?"

"The Grateful Dead. Their album American Beauty."

"I think I've heard of them. But never heard them."

He hadn't heard the Grateful Dead? He only thought he'd heard of them? What sort of heathen was this? They were my musical gods. I almost lived my life by them. They spanned all my moods from frivolity to anguish. They were my stimulant and my painkiller.

"That song," I explained, "Attics of my Life. The lyrics are by Robert Hunter. He wrote a lot of their lyrics. And he's a poet in his own right, too."

"How does it go on? Or is that all of it?"

"Oh no. Several verses. Look, why not listen to it? Sung properly, with the band. I've got the CD with me."

"But I don't want to waste your time."

Spreading the gospel to the heathen was never a waste of time. Even more to the point, here was a personal opportunity emphatically not to be missed.

"No problem at all. Let's go to the common room."

We found two chairs. I dug the discman out of my bag, gave him the headphones, set the right track. and sang along in my head.

In the attics of my life,

Full of cloudy dreams unreal,

Full of tastes no tongue can know

And lights no eye can see,

When there was no ear to hear

You sang to me.

I have spent my life

Seeking all that's still unsung,

Bent my ear to hear the tune

And closed my eyes to see.

When there were no strings to play

You played to me.

In the book of love's own dream

Where all the print is blood,

Where all the pages are my days

And all my lights grow old,

When I had no wings to fly

You flew to me.

You

flew

to me.

In the secret space of dreams

Where I dreaming lay amazed,

When the secrets all are told

And the petals all unfold,

When there was no dream of mine

You dreamed of me.

As I sang in my head, I watched him. He was sitting there with eyes closed, his heavy eyebrows bent in concentration as he penetrated the American accent. He looked . . . what was the word? Velvety was the best I could rustle up. I had to lean forward to disguise what was going on in my jeans.

"I like those words," he said when the track ended, "very much. How could I get hold of a copy? I wonder, could you possibly dictate them to me? It would be easier than trying to write them down from the CD."

"Easier still to print them off the web. They're all there, all his lyrics for the Grateful Dead. Let's see if there's a computer free. I've got Robert Hunter's website bookmarked at home, but it'll be easy to find."

Off to the computer room, surreptitiously adjusting myself. Google obliged instantly.

"There you go. Attics of my Life. Let's print it off."

"No, don't bother, thanks. I'll just note the URL and do it at home. And read the rest too."

"It'll take you some time. There's a lot of it."

"You're a fan of his, that's obvious. Can you tell me more about him? Once I've read his stuff?"

I had two reasons for educating him, and no hesitation on either score.

"Course. No problem."

"Thanks very much. Well . . ." He paused as if uncertain how to wind up our chat. "I've finished here for today. I'd better be getting home."

"Same here." I stood up and looked at my watch. "Oh, shit!"

"What's up?"

"Missed my train. Never mind. I'll do my homework in the library and get the college bus."

"But I made you miss your train. I've got a car. I'll run you home."

"Don't bother, thanks. I'll be OK." But I hoped against hope that he would insist.

"No, I insist. It'll save you time, the way the bus stops at every lamppost. Where do you live?"

"Porthmadog. Where do you live?"

"Clynnog."

"But . . ."

Pwllheli to Clynnog via Port is a long way, two sides of a bloody big triangle. But I looked at him, and saw that he wanted to drive me. And I knew that I wanted him to.

"OK, then, if you really don't mind. Thanks."

I do not know if a tree

remains a tree when

I turn toward a cloud --

nor if my love is love

or infatuation of the eye

with the bright gilding

of the heart's foundation

by whose inexact light

I happen to see another.

Sentinel, Fifth Watch, 1991

He gave way. We picked up our bags and went out to the car park and the MG. As we shoehorned ourselves in, a posse of macho types was eyeing us.

"I reckon they're envious," he said.

"Or pitying, that I don't drive this thing the way they think I ought to drive it."

"I'm glad you don't. I don't like speed, or noise. Not of that sort."

"Nor me." So we agreed on that too. "I'm sorry, I don't know your name."

"Kenneth. Kenneth MacAlpine."

I almost drove up on to the pavement. I had overheard people at college saying interesting things about Kenneth MacAlpine, but had not hitherto had a face to put to the name. Were those macho types sneering at me for consorting with the likes of him? This isn't keeping your head down, Cilmin. It's sticking it up above the parapet, a target for snipers.

"Oh," I said, trying to push my fears aside. "Same as the Scottish king?"

"That's right. You've heard of him, then? Not many people have. Not here."

"Comes of doing history. So you are from Scotland?"

"Yes. We came down five years ago, Mum and me."

"No brothers or sisters, then?"

"No, just me."

"Same here. What brought your Mum here, then?"

"She works for the Edinburgh Woollen Mills, and they put her in charge of their shop in Port."

"Ah. And you prefer Kenneth, not Ken?"

"Yes. Not Ken, please. And definitely not Kenny." I almost felt him shudder. "And I don't know your name, either," he pointed out.

"Sorry. Cilmin. Cilmin Glynne-Williams."

I was glancing at him, and saw him blink.

"Cilmin? How do you spell it?"

I spelled it out.

"Never heard that one before."

"Not surprising. I've never heard of anyone else called Cilmin, either."

"Where does it come from, then?"

"Oh, it's an old, old name, from the top of the family tree. Cilmin Droed-ddu, Cilmin of the Black Foot. A semi-mythical character. Supposedly founder of the Fourth Noble Tribe."

There was a pause as Kenneth, I sensed, stored that away to pursue later.

"And the Glynne-Williams -- that's a double-barrelled surname?"

"Yes."

"I've never met anyone double-barrelled before, either. It sounds like an old county family."

How right he was. "Well, we were once. Cousins of the Glynnes of Glynllifon, who became the Wynns, who became the Lords Newborough. But that was centuries ago. We're just minor gentry now."

And thoroughly inbred and on the way out, I thought, but did not say so. Best shift the subject back to him.

"So you were at Ysgol Eifionydd in Port before coming to the college?"

"That's right. Where did you go? Glan y M�r?" That is the secondary school in Pwllheli.

"No. Ysgol Dyffryn Nantlle. In Penygroes."

"But . . ."

I knew exactly what he was going to point out. That Penygroes, like all the secondary schools in Arfon, has a sixth form. None of the schools in Dwyfor or Meirion does. Which is why Coleg Meirion-Dwyfor exists, as a sixth-form college for everywhere in the Pwllheli and Porthmadog area and southwards. Ordinarily I would have stayed on at Penygroes. I willed Kenneth not to ask why I had left it.

And he did not ask. Instead, we compared notes about the college, me with a year's experience of it, he with only a few weeks'. It turned out that he was doing chemistry, physics, maths and biology at AS.

"I envy you that," I confessed, "in a way. But I'm hopeless at science. My GCSE results were dire."

"What are you doing, then?"

"A-level history, music and English literature."

"And I envy you that, in a way. I like history. And I haven't read much literature, not of that sort. And I'm probably rather narrow in my music."

"Nothing but the Grateful Dead?" I asked teasingly, daringly.

"Not much else," he admitted with a smile. "The Byrds, a bit. Bob Dylan, a bit. But I've got a one-track mind."

He coughed as if he had said something embarrassing, and went on quickly.

"What music do you go in for?"

"Rather different. Classical. Especially baroque, anything from Monteverdi to Mozart. I've got a one-track mind too."

And so on. Small-talk, but we got on famously. He was as he looked, gentle and intelligent. No hermit like me, but no great socialiser either. Confident but modest. Self-contained.

As we crept into Porthmadog in the tailback of traffic on the Criccieth road he began to give directions, "Left at the roundabout."

We passed the Coliseum cinema, showing some ancient film, and he nodded at it.

"I don't often go there. But there's bugger all to do here, you know."

"Ten times as much as in Clynnog. It's only a small village."

"Mmmm." It was not clear if he was sympathising or approving. "Second left beyond the level crossing, into the estate. Y Ddol. Yes, here. Know what we call this?" he added mischievously. "Midmadog, because it's between Porthmadog and Tremadog. Next left."

Nineteen-fifties housing gave way to nineteen-eighties.

"Left again, into Maes Gerddi. Follow the curve. Last box on the left."

It was indeed a cramped and flimsy box of a house, to one born and bred in seventeenth-century space and solidity.

"I've got a book," he said abruptly as I pulled up, "of Robert Hunter's poetry, if you'd like to borrow it. Do you want to pop in? Mum won't be home for ages."

Was that a bait? If so, a bit early to rise to it.

"No, I'd better be getting home, thanks. But I would like to borrow it, please. I'll wait."

He seemed disappointed, but grabbed his bag, levered himself out of the car, let himself into the house, and soon reappeared.

"Here you go. I hope you'll like it. And thanks for the lift, Cilmin. See you tomorrow?"

"Yes. I'm in first thing. Till then!"

I had not felt like this for years. Wrong -- I had never felt like this. On a high, I drove home via Pant Glas, faster than usual, almost falling foul of the police speed trap at Bryncir. I was already deep in nefarious plans. No, not nefarious. Calculated, rather. Caution was called for, extreme caution, but at the same time boldness. Boldness? From me? It sounded laughable. But already, on impulse, I had taken the boldest step. I found room to hope that it had not been a crashing mistake, that I was not inviting public curiosity, that . . . that he really was what he seemed to be.

Over dinner I checked with Mum and Dad. It must have been seven years since I last had a friend to stay, but they exchanged a single glance and agreed without hesitation. Although not a word was said about motives or reasons, they understood. They often drove me mad, but in this area they were wonderful. Then I settled down to Robert Hunter on the web and in print. Much of his work, I found, spoke to me.

Just as Kenneth spoke to me.

While you were gone

These spaces filled with darkness.

Next day, Wednesday, I buttonholed him in the break between first and second class.

"I've read quite a bit of Robert Hunter. It's great. And I'd love to hear more about him. But my timetable's pretty full for the rest of the week. Um, could I persuade you to come and stay at my place over the weekend?"

He was looking at me wide-eyed, and replied with heart-warming speed.

"I'd like that. Thanks very much. But I'll have to clear it with Mum. Let you know tomorrow?"

"Of course. If it's OK, I'll drive you back here on Monday morning, so bring everything you need on Friday. And Kenneth . . ."

This was tricky, but very necessary.

"I've got to say this, because we need to know where we stand. I've heard people talking about you. I hope I'm not speaking out of turn, but I get the impression it's no secret. That you're gay."

"No, it's no secret. Not now. Do you mind?"

"Not in the least. I've no problem with it. But at Lleuar . . ."

"Lleuar?"

"That's the name of our house. At Lleuar you'll be in a spare room, and I'll be in my room. I don't leap into bed with boys, or men. OK?"

"OK by me," was all he said.

But his face visibly fell. Qualms beset me. Had I misjudged him? Was he, after all, just out for sex? Wait and see, was the only answer. And meanwhile give him the benefit of the doubt.

Reach out your hand if your cup be empty,

If your cup is full may it be again,

Let it be known there is a fountain

That was not made by the hands of men.

Ripple, 1970

Mum was a bit of a name-dropper. A whopping big name-dropper, in fact. Whenever Lord or Lady Thingummy patronised her shop, I heard of little else for a week. So when I told her I had been invited to stay with an old county family, and promised her (before she could ask) that it would not be a weekend of torrid sex, she preened herself in reflected glory and readily agreed. Maybe she also welcomed the extra time with her gentleman-friend, without the bickerings that were the norm when I was around.

As for Cilmin, I already liked him and wanted to build up the friendship. He could become -- he looked like becoming -- as good a friend as Megan. And I already lusted for him as a great deal more than a friend. For the rest of the week my mind, as I jerked off first thing in the morning and last thing at night, was full of his image. Despite his very plain statement, moreover, I had this feeling that he too was after something more than friendship, that even as a soul-mate he might not be wholly inaccessible. But never before had I trodden this road, and I had to tread it with the utmost care.

His parents, Cilmin had told me a trifle apologetically, liked, er, to do things the old way, and would appreciate it if I brought a jacket and tie. Tie, eh? I had not worn one since my last day at school. By Friday afternoon I was in a state of high expectancy and some trepidation. After my last class I found Cilmin slumped in a chair in the common room, staring into infinity. I sat down beside him.

"Anyone there?" I asked after a minute of not being noticed.

That jolted him back to earth, in confusion.

"Sorry, Kenneth. I was miles away. Very rude of me."

"Not rude. We all need to go there. Well, I do, and I can't dictate when."

He was still patently embarrassed, and to help him over it I quietly sang a song, quietly both to avoid public attention and to spare him the worst of my voice.

"Wake up to find out

that you are the eyes of the world,

but the heart has its beaches,

its homeland and thoughts of its own.

Wake now, discover that you

are the song that the morning brings,

but the heart has its seasons,

its evenings and songs of its own."

He listened with a grave air of appreciation and, I could have sworn, relief -- not relief that I had covered his embarrassment, but at something else that eluded me.

"Yes," he said thoughtfully. "Homeland and evenings. I do spend a lot of time there." He snapped out of brooding into briskness. "Right, then. Ready to go?"

Out to the MG. North from Pwllheli, through Y Ffor's single unprepossessing street, skirting Llanaelhaearn and the shoulder of Yr Eifl, under the screes of Moel Penllechog, and into the scanty village that was Clynnog. Left into a lane immediately short of a large church with a stumpy tower, right between stone gateposts on to a crunching gravel drive, through a small plantation of big trees. And there stood Lleuar four-square ahead.

"Bloody hell!" I muttered.

We swung to the right, then left round a wing, to pull up at the front door. I gawped, almost expecting, from my vast experience drawn from films, to see a butler or footman emerge to take charge of our luggage. Cilmin read my mind.

"No servants, I'm afraid," he said. "It's an infernal nuisance, but one just cannot find them these days."

I looked at him suspiciously, but his face was deadpan. When I looked back, his parents -- they must be his parents -- were coming out of the door, a big black labrador cavorting round their feet. Father, a forty-ish version of his son, in tweed and twills. Mother, ultra-elegant in hair-do and make-up, in heather-coloured cashmere and skirt. Cilmin introduced us, the dog introduced himself, and they all welcomed me with warmth. I did my best to reply in proper form.

"It's very good of you to invite me, Mrs, er . . ."

I was visited by a sudden and ghastly fear that they were really Sir and Lady, not Mr and Mrs, and that Cilmin had forgotten to tell me.

She laughed, but kindly. "Oh, call us Priscilla and Goronwy. Please do, Kenneth. We don't stand on formality here. Do come in. Cilmin will show you your room. I'm sorry there's nobody to bring in your luggage. It's an infernal nuisance, but one just cannot find staff these days."

Cilmin, pink in the face with the effort of keeping it deadpan, acted as footman and carried my bag himself. My room was next to his, with a view up the coast to Dinas Dinlle and clear across the sea to Anglesey and Ynys Gybi. Next to mine was a dingy bathroom with an antique tub and basin and loo but also, incongruously, a new wall-mounted fan heater and a shiny shower-head over the bath.

"This is just for us. There's another in the south wing where Mum and Dad sleep. If you'd come four months ago there wouldn't even have been a shower. Such things probably hadn't been invented when my great-grandparents put the plumbing in." In my turn I hid a grin. "But I begged for this shower for my birthday present, and life's much more civilised now. Right, let me show you round the rest of the house and the garden."

Lleuar proved to be twin-gabled, twin-winged, built of solid stone -- no pebble-dashed concrete blocks or plasterboard at Lleuar -- with tall chimney stacks and all the authority of age. Yet, grand though it was to my modest eye, it was far from a stately home. It was not even large, as large houses go. But these things are relative. Our little box would fit into it ten times over, and every room was at least twice the size of our counterpart.

"Seventeenth century, mostly," said Cilmin, and it looked it. The hall and reception rooms were oak-panelled, small-windowed and dark, with open fires warding off the early October chill. "No central heating," said Cilmin. Gentle decay pervaded the place. Carpets and curtains and upholstery, though not quite tatty, were threadbare and faded. The garden, while not unduly large, was only half-kempt, with grass in need of cutting and beds in need of weeding. "No servants," said Cilmin, and this time he could enjoy the joke.

"It's five o'clock," he added, looking at his watch. "An hour or so till it gets dark. I could show you the church, but we'll see that on Sunday. If you don't mind coming to Matins, that is -- it's in English this weekend. Evensong's in Welsh, and we don't go to that. So what about taking Rasmus for a walk now? Did you bring your boots?"

"Fine by me. Yes, I did."

So, while Rasmus bounded ahead, I walked by Cilmin's side down the lane strewn with autumnal leaves, venturing the first tentative steps towards discovering him, alert for any hint of the direction he might take, ready to stop, ready to sprint. We passed several large and ancient holly trees.

"There are lots of them round here," said Cilmin, "which is right and proper."

"Why right and proper?"

"Because that's what Clynnog means. Celynog. The place of holly."

A comforting and homely name. The berries were beginning to turn, some still green, some amber. Like traffic lights. Green, carry on. Amber, be prepared to stop. Message understood, though it was not Cilmin's.

Five minutes brought us to the coast. The sea was simply sea, sullen and grey. The narrow beach beneath gravel cliffs was shingly and disappointing.

"It's lousy for bathing," said Cilmin. "It's uncomfortable to walk on, it shelves steeply, and the currents are fierce. And the farm buildings up there" -- he nodded to a cluster a few yards inland -- "have been turned into holiday homes. Down here, in summer, it's a-squawk with kids."

No message on the coast, then. We retraced our steps towards the more uplifting view inland, a gentler landscape than mine at Port. The coastal plain a few hundred yards wide. Lleuar and its trees and, just beyond it, the church. The huddle of the village. The lower slopes with their jumble of small fields. The mountain wall. Then open acres of moorland, pale green even in the dwindling light. Finally, standing distant watch, the knobbled summit of Bwlch Mawr, for all its sixteen hundred feet a hill rather than a mountain, benign rather than stern. Nature might one day reclaim the meadows and tumble the buildings, but the essence of the scene would remain.

We left the lane for another track, which led us to a crude monument surrounded by a battered railing in the middle of a field. Four big upright stones carried a flatter one on top, maybe nine feet long, like a giant table-top almost at eye level.

"Meet the Bachwen dolmen," said Cilmin. "Neolithic. About 3000 BC. There would once have been a barrow round it and over it. A great mound of earth, like this." He demonstrated with his hands. "These stones were just the burial chamber in the middle. And look at these cup-marks." He pointed to the table-top, pocked with a hundred little round depressions.

"What were they for?"

"Nobody knows. Some sort of magic, I suppose. Something ritual. Maybe they put offerings in the holes, to placate the spirits of the people already inside, to apologise for disturbing them. I'm sure there are spirits here. I always find it a spooky place."

So did I, though their presence seemed benevolent and earthy. Yet Rasmus did not like them. His tail was between his legs.

"But the holes," I objected, "would've been covered by the mound."

"Ordinarily, yes. But they kept reopening the thing for more burials, generation after generation. Like a crypt in a church."

Now that word crypt, like aviary, always sets me off.

"What's the joke?"

Oh dear. First decision to make. Did I mind Cilmin knowing about my dirty mind? He seemed so serious a young man. Not prim, but serious, restrained, austere. He did smile, but I had never seen him laugh, not properly. I had never yet heard him use the earthy language that was normal to me. Maybe he had religious scruples. After all, he went to church. Be honest, though. Let him be himself, and I could not in honesty be other than myself. I took the plunge.

"Well . . . Crypt always reminds me of a limerick. A very funny one. Well, I think it is."

"Let's hear it, then."

"Well, it's dirty. Very dirty, and gay. Do you mind?"

"No. Let's hear it."

I felt a fool as I solemnly recited.

"From the depths of crypt at St Giles

Came a scream that resounded for miles.

Said the verger, 'Good gracious!

Has Father Ignatius

Forgotten the Bishop has piles?'"

The ghosts, I sensed, approved, but Cilmin's laugh was not very convincing.

"What the word reminds me of," he replied, "is that silly little sentence, 'The cat crept into the crypt and crapped.'"

I laughed in turn, feeling awkward. Luckily Rasmus rescued me. He had had enough of the spooks and was insisting that we leave. Through the fading light we ambled back to Lleuar. Cilmin gave me first use of the shower, and when he had done he collected me. Both of us were now resplendent in jacket and tie.

"Right, if you're ready, let's go down to the drawing room for some sherry."

I had not felt it hitherto with Cilmin, but at Lleuar, in the company of the Glynne-Williamses, I was conscious that I came from a different walk of life. Drawing room, eh? We called it the lounge. Sherry, eh? I had no more than heard of the stuff. Indeed I had hardly drunk any alcohol at all. There was plenty of gin and whisky in our house, but it was reserved for Mum and her gentleman-friend. From the noises in the kitchen, Priscilla was evidently cooking, but Goronwy was in the drawing room and poured us a sherry apiece, and very pleasant it proved to be. Although he must have known it from my accent, or my name, or from Cilmin, he pretended to be surprised that I was Scottish, and we talked about Edinburgh, which he knew a little. Then Priscilla called us in to the dining room for dinner.

Dinner, eh? At home we called it tea. The food was great -- four courses in all -- but there were pitfalls. Each place had an array of silver. I watched carefully and tried to use the right knives and forks. There was a choice of drinks. White wine, I saw, went into tall glasses, red into round ones, water into tumblers, all of them different from the sherry glasses. But even if I had got it wrong, I had the impression they would not have minded. Traditionalists they may have been, but not snobs. Not real snobs. Humble though my background was, they seemed to envelop me in a warm blanket of approval. I wondered why. And they were all generous in including me in their talk. The message here was good.

Goronwy told Priscilla that I was a Scot.

"What's more," added Cilmin, "he's named after Kenneth MacAlpine the Scottish king."

His parents had clearly never heard of him. "When did he live, and what did he do?"

"Ninth century, I think. He started uniting Scotland into a single kingdom."

That did interest them. "Really? At the same time as Merfyn Frych started uniting Wales, then."

I, in turn, had never heard of Merfyn Frych.

"He was a Celtic prince," explained Cilmin, "from the Edinburgh area, as it happens, who married into the dynasty of Gwynedd, and who married his daughter off to the prince of Powys. So things began to come together for the first time. And one of his lieutenants was Cilmin Droed-ddu, who settled at Glynllifon."

I knew about Glynllifon, of course. It was only a few miles north of here, and it was the Newboroughs' seat, a proper stately home. Or rather it had been. It was now the third campus of Coleg Meirion-Dwyfor, where they taught agriculture, forestry, animal care and engineering. Its wide acres of grounds were a country park open to the public. There was a museum in the stables. Signs of the times, all of them.

"And as I told you, Cilmin was ancestor to the Glynnes of Glynllifon who ultimately became the Newboroughs. And he was also ancestor to us. We're how many generations down from him, Dad? Thirty-five?"

"That's right, for me. Thirty-six for you."

Thirty-six generations. My mind boggled.

"But why Cilmin Droed-Ddu?" I asked. "Why Black-foot?"

Goronwy laughed. "There are various legends. The one I like best is that a sorcerer asked him to go to Tre'r Ceiri and rescue a book written by no human hand, which was guarded by demons. He warned him not to touch water on his way back. So off Cilmin went, and after a brisk tussle with a giantess he grabbed the book and hurried away, with a horde of demons in hot pursuit. He came to a stream which he knew no demon could cross. Beyond it lay safety and, just in time, he leapt across. But in scrambling up the bank his foot touched the water, and a sharp pain ran through his leg, and his foot turned black. A black leg has been part of our coat of arms ever since. Look at your plate."

I had noticed that every plate, large and small, was of porcelain, with an inch-high shield painted on the rim. The quarters at top left and bottom right indeed had a black leg. The others had a two-headed eagle and three burning sticks. These were explained to me, as was much more about the family tree, but I took little of it in. I was happily mellow after a glass of sherry and two of wine. Was I drunk? I certainly did not feel in full control, and distrusted myself. Tempted to say more and more, I decided to say less and less.

When the meal was over, Cilmin, all unsuspecting, insisted that we wash up, and banished his parents to the drawing room with their coffee. I was feeling yuckier still, but it was only when we had almost finished, and when I had almost dropped a priceless plate, that I had to run, and run urgently.

Cilmin tracked me to our bathroom, where he found me at the mouthpiece of the great white telephone to God, saying goodbye to my dinner. He was sympathy itself, and even apologetic.

"I'm sorry, Kenneth. I'm used to it, and it never crossed my mind that you weren't. Look, wash your mouth out, and drink plenty of water to dilute it."

I was feeling bad about my performance, very bad indeed. Had I fatally disgraced myself? I was also feeling better, but not up to company.

"Oh God. It's me that should be sorry, Cilmin. I'll know for next time. But I'd best get to bed. Say thank you to your parents for the meal, would you? Don't tell them I threw it up. Just that I'm knackered. Which is true."

That night, for once, my right hand remained unexercised. I slept like a log and woke late, feeling a touch delicate but -- was it because I had cleared my system at an early stage? -- no worse than delicate. I was fit, at least, to make up for the omission of the night before. Then Cilmin knocked at my door and enquired how I was, and we came down to find that Priscilla and Goronwy had already gone into Caernarfon to shop. Over a leisurely breakfast we debated what to do with ourselves. I remembered that Tre'r Ceiri had been mentioned over dinner. Giants' Town, it ought to mean, and I asked Cilmin for details.

"Well, let me show it to you. Much better than trying to describe it. It's a great place. A ten-minute drive, then a half-hour walk. Are you up to that?"

He pointed it out from the landing window, the leftmost of the three peaks of Yr Eifl. Yes, I ought to be up to that and, after throwing some sandwiches together, off we went. It turned out to be a forty-five-minute slog, not a half-hour walk, but well worth the effort. We found ourselves at an Iron Age hillfort surrounded by dry-stone ramparts ten feet high, its interior dense with the tumbled walls of round huts. By the cairn at the highest point we sat to eat our lunch and drink in a vista as spectacular as the fort. It was a superb day, and warm for the time of year. To the north we could see the whole of Anglesey, and only four miles away picked out Clynnog church and Lleuar. We looked east to my own Moel y Gest and the real mountains beyond. Southwards we saw right down the Llŷn peninsula and clean across seventy miles of Cardigan Bay to the pencil line of the Pembrokeshire coast. Only to the west were we thwarted by the main peak of Yr Eifl obstructing the distant view.

"Pity about that," said Cilmin. "It blocks out the Wicklow Mountains."

"What, in Ireland?"

"Yes. On a day like this they're bound to be visible. Want to climb the next peak to see?"

"Mmmm. Not sure I feel that energetic."

"OK. Plenty of chance in the future."

So he was looking ahead to more outings together, was he? That was encouraging. I was evidently forgiven for yesterday. Not a soul was in sight, not even demons or a giantess. The only sounds were the breeze in the heather and bleatings of distant sheep. We sat, backs to the cairn, side by side, contented.

Cilmin broke the silence.

"Tell me about Robert Hunter, then. There's been no chance yet.

Sometimes the light's all shining on me,

Other times I can barely see."

I painted in the background. How the Grateful Dead had started in 1965 under the lead of Jerry Garcia. How they had ended thirty years later with Jerry's death, though some of them were now playing together again. How they had fused rock, blues, country, jazz and Lord knows what else into a new sound, creating a legacy of great musical substance. How Robert Hunter had joined them as a non-performing songwriter and raised the level of their lyrics far above that of any other band. How they had become an international name and, apart from the Rolling Stones, had been probably the longest-lasting rock group ever. How their concerts had been fired by the interaction between band and audience, both of them fuelled high on LSD or worse.

At that, Cilmin stirred. "I'm not comfortable with drugs. Are you?"

"No. I'm not. I'd never want to get high on anything, especially after last night. But I suppose it was inevitable, in the circumstances. Given the pressures they were under. And in their psychedelic period it was an inspiration too. What do you make of the GD's music?"

"From what little I've heard, it's not really my scene. But I can see myself getting to like it. Hunter's lyrics go well with it. And it goes well with them."

"And you like them?"

"Very much. They're impressive. Some are fun. Some are nonsense. Some are profound. Some are obscure but seem to hide a very important meaning, if only one could get at it. And that's even more true of his poems."

"I know what you mean.

One watch by night, one watch by day,

If you get confused, listen to the music play."

He chuckled. "That's from Franklin's Tower, isn't it? And I like the themes that run through so many of them. I'm not one for analysing poems clinically. I go more by what they say to my emotions. And his say a lot. About light and darkness, particularly. He's got so much about the light of understanding and knowledge and grace and bliss, which so often slips away when we try to reach for it. And about their opposites."

"Yes. I know what you mean about that too.

What fatal flowers of

darkness spring from

seeds of light?"

More good messages. And so we went on, at a length which cannot be repeated here, until the falling temperature drove us down. We took a supposed short cut through the heather and found ourselves in a boggy patch. Cilmin tried to leap across a pool of peaty water, landed short, and pulled himself out with one leg dripping.

"Cilmin Droed-ddu!" I cried.

I was creasing myself with laughter, and so was he -- proper laughter, for the first time in my presence. There was much about him which I did not understand, and this episode gave me confidence to ask further, as well as excuse. As he sat on dry ground, boot off, wringing out his sock, I raised a matter which puzzled and, I admit, slightly disappointed me.

"Cilmin. You know about my dirty jokes. And I'm always using bad language. Well, earthy language. So do all my other friends. But you don't. If I'd fallen into a bog I'd have said shit. Or worse. All you said was bother. Is it because you're, um, religious?"

"Oh, I'm not religious. I only go to church because Mum and Dad do, and because I like the vicar. Religion doesn't come into it. But earthy language . . . well, I'm not a prude either, I hope . . . let me think."

He pondered.

"I do use it, you know. Occasionally. I seem to remember saying crap yesterday."

Well yes, he had. But that was hardly . . .

"But I suppose bad language just isn't my habit. I don't feel a need to use it. We all express ourselves differently. I might as well ask you why you do use it."

It was my turn to ponder, relieved that he had not mentioned social differences.

"Well. My Mum's pretty strict. Not churchy. But she tries to keep me on quite a short rein. So maybe it's my form of protest. Though I don't use it in front of her -- she'd throw a fit. And I draw the line at the f-word, at least as an expletive. Some of the macho types at college throw it around like confetti. That's just pointless."

"Agreed. And perhaps I don't use earthy language because my parents give me plenty of freedom."

"But it doesn't offend you if I use it? Or tell my dirty jokes?"

"Oh Lord, no. Not a bit. You be true to yourself. You say what you need to say, as you need to say it. Please do, Kenneth. It's all a part of you. I'd never want you to change your habits just for me."

Hmmm.

He pulled up his wet trouser leg, exposing his shin damply plastered with black hair. I stared at it, mentally drooling, stiffening down below.

"Anyway," he said, wriggling his foot into his sock, "I've got a dirty joke for you, in return for yesterday."

That was a step forward. "Let's hear it, then."

"Well, there was this innocent young assistant priest at a Catholic church, and his boss -- let's call him Father Ignatius again -- went away for a few days and left him in charge. All went well until confession time. Father Ignatius had left him a list of standard sins and the standard penances to give for them. No problem at first. A woman who confessed to lusting for the bloke next door -- that's ten Ave Marias. A man who confessed to nicking ten quid from the office cash-box -- let's see, sliding scale, ten quid, that's twenty Paternosters. Then a man who confessed to having a, er, a blow-job. Blow-job? The priest had never heard of it, and couldn't find it in the list. So he stuck his head out of the confessional and beckoned to an altar boy.

"'Hey, sonny, do you know what Father Ignatius gives for a blow-job?'

"'Course I do. Two Snickers and a Coke.'"

I laughed. It was a good joke, and he had told it well. But I was puzzled. Why, I wondered as he laced up his boot, hadn't he trotted it out yesterday, as a follow-up to my limerick? It would have been far more relevant then. And he had noticeably winced at using the word blow-job. On top of that, I had met the story before. If you asked Google for 'gay jokes,' this was one of the first that came up. I knew. I had tried it the other day.

Hmmm, again.

So back to Lleuar, another walk with Rasmus, shower, and dinner. This time I knew my limitations, and this time the conversation was on science; once more, I thought, for my benefit. We then sat down companionably, Cilmin and I, side by side at his desk, to clear our weekend homework out of the way. His room was as neat and tidy as Cilmin himself and, with the gas fire going, it was snug. There was music in the background. I had riffled through his collection, which was all classical and unfamiliar, and left it to him to choose. He chose something he called the Brandenburgs, as orderly and restrained as Cilmin himself, and fun.

He was writing an essay on his computer, and I longed to look at its History record to see if he had visited Google last night. But of course I could not. I finished my work before he did, and sneaked a look at him as he sat intent on his monitor. My eyes travelled slowly across his face. The narrow pink strip in front of his ear before the shadow started, a single short black hair at its edge which he had missed in shaving, a dusting of down on his cheekbone, the long narrow nostril, the satin of the nose above, the lips moving slightly as he dictated to himself. Those lips . . . I grew uncomfortable. And I had been staring too long.

I got out my latest New Scientist, which had arrived the day before but was still unopened. 'Which way is up?' was the lead article, all about the quantum world and Schr�dinger's cat -- very much my cup of tea, but difficult. Cilmin noticed.

"New Scientist? I've heard of that. Is it good?"

"Brilliant. It covers everything you can think of, as intelligibly as they can make it. A lot of it's still over my head, but it keeps me up to date with the latest findings. Very useful, now that I'm specialising. Mum gave me a year's subscription for my birthday."

And so to bed, to the usual accompaniment.

Sunday morning took us, in jackets and ties, to church. It was clearly a weekly ritual for my hosts. The building itself, spacious and bright with big windows, felt hospitably open.

"It was a monastic house, this," whispered Cilmin helpfully in my ear as we took our seats in the front row, "and rich -- a major staging point on the pilgrim trail to Bardsey. That's why its full name is Clynnog Fawr, Great Clynnog. And that's why the whole thing's so large and light and airy, compared to most of the dark and poky little churches round here."

I was a heathen, wholly non-religious, wholly at sea in any service other than the dour Scottish funerals and weddings of which I had fair experience. I had to follow Cilmin's lead in sitting down and standing up. But, to my surprise, the service was lively, livelier even than a Scottish wedding. And, to my profound astonishment, the vicar's sermon, short, well-argued and witty, was a devastating attack on creationism.

"When the Methodist minister hears about that," whispered Cilmin delightedly in my ear, "he'll be hopping mad. There's a running battle between them."

We filed out with the rest of the congregation and I was introduced to the vicar, who welcomed me with more enthusiasm than I deserved. Gwilym was his first name, and nobody mentioned his surname. Priscilla and Goronwy peeled off home, but Cilmin offered me a guided tour. He led me back inside, through the tower and along a vaulted passage to an otherwise detached little chapel.

"Scream when I bore you. But I'm proud of this place, somehow, and can't help showing it off. It all began around 630, with dear old St Beuno. He came from the south, where he'd been a buddy of Dewi Sant -- you know, St David -- and he set up shop here. And like Dewi he was a right old evangelical, strict as they came, and up here in Gwynedd he became very influential. When he died he was buried here. So this is his grave chapel, Capel y Bedd, which was a place of pilgrimage in its own right. They've found the footings of the original building under the floor -- these marks on the flags show where. This building's a replacement of 1500, give or take a few years. So's the whole of the church, come to that. The original church was presumably under the present one."

He took me back to the church proper. We admired the old furnishings. But what interested me most was the north transept. Here were the tombs of the Glynnes and Glynne-Williamses going back to Tudor times, carrying the same coat of arms with the black legs. I found myself marvelling at the length of Cilmin's pedigree, at the mind-blowing stability of one family in one place. I could not have named any of my own ancestors beyond my grandparents. Rabid old dissenters they had been, too, as were my aunts and most of my cousins still, though at least Mum had broken free. I much preferred this liberal and open atmosphere. We ended up beside the altar at a memorial to the William Glynne who died in 1609. It showed him on his knees with a brood of twelve diminutive offspring charmingly strung out in line astern, like ducklings behind a duck. We laughed, and in this tolerant place our laughter did not feel amiss.

"Let's have a look round outside," Cilmin suggested.

"Will it take long?"

"Only a few minutes. Why?"

"Because I need a pee."

"Sorry, no loos here. As they say on the incontinence hotline, can you hold, please?"

It was so unexpected from Cilmin that it caught me off guard, and I guffawed out loud. In Scotland, lightning would have streaked down from heaven upon anyone guffawing in church. Here, nothing happened, and it left me on a high.

"All right," I agreed. "I'll tie a knot in it."

Cilmin led the way out of the porch and turned left, which offended me.

"Hey! Dinna gang widdershins aroon a kirk!"

"Eh?"

"Sorry. Being frivolous and Scottish. Don't go widdershins round a church. It's unlucky. I don't know much about churches, but I do know that. Don't you?"

"Widdershins?"

"Anti-clockwise."

"Oh. No, I didn't know. Why?"

"Well, the opposite is deasil. That's Gaelic. Clockwise, following the sun. Something to do with old Celtic ritual, following the sun. You ought to know about that."

He laughed. "But I don't. OK, let's be good Celts, then, and go deasil."

So we turned right, abandoned the path and threaded our way through thickets of gravestones commemorating Gwladus Evans, beloved wife, and Ebenezer Pritchard, Pant, cobbler. Most were in Welsh, and many carried verses which I found hard to translate.

"I saw an In Memoriam once," I remarked, "which said,

The last trump sounded,

St Peter said 'Come!'

The pearly gates opened,

And in walked Mum.

Can you credit it? Are these Welsh verses any better?"

Cilmin was smiling. "Well, they're more, um, literary, but a lot of them are pretty hackneyed. Yet some englynion are good. There's one by Tegidon -- where is it? Oh yes, here -- to a father and his young son."

Yr eiddilaidd ir ddeilen -- a syrthiai

Yn swrth i'r ddaearen;

Yna y gwynt, hyrddwynt hen,

Ergydiai ar y goeden.

I struggled with the Welsh, and Cilmin came to my rescue.

"'The sickly leaf, still green, fell to earth. Then the wind, the ancient tempest, struck at the tree.'"

I was jolted out of my flippancy.

"Oh God. That gets you in the guts."

Cilmin was watching me with a curious expression. What was he thinking? That this boy is more than rock music and dirty jokes and earthy language? For a moment I wanted to cry.

We worked our way to the corner of Capel y Bedd. There stood a tall slab with a simple sundial carved on it and a hole where the pointer had been.

"About a thousand years old," said Cilmin. "Let's see if it still tells the right time."

He stuck his pen into the hole, and the shadow fell down the vertical line.

"Oh dear," he said. "That ought to mean twelve, but it's nearly one."

"Summer time. It's really twelve, by God's Mean Time."

"Oh, of course. Silly of me. But lunch is at one. We'd better hop it."

But as we left the churchyard by a different path, Cilmin paused by a flat slab surrounded by a low spiked iron railing.

"This one always touches me too. Sorrowing parents struggling with unfamiliar English."

Here Lie the Remains of John Jones son of Griffith Jones of Wern by Mary his wife was Drownded on the 19th August 1796 Aged 14 Years.

Also William Jones his brother happened of the same Accsidence in the same time, in the 13th year of his Age.

How had it happened? Swept away from the beach by the currents? What had those boys been like? Carefree and cheerful, like me at that age? Oh God, the unfairness of life. Our eyes met in silent agreement, and we went soberly back to Lleuar, and the loo.

After a 'light cold luncheon' for which Priscilla apologised, Cilmin dragged me out again, minus tie, to a place he thought I would like. He too sounded apologetic, but I did not mind in the least -- simply to be with him was inspirational enough. This time we drove south to a village named Llangybi. We parked beside the church, cut through the churchyard, over a stile and down a field. At the bottom ran a stream bridged with crude slabs, and across another field lay a small cluster of ruins. The slope beyond was thick with ancient beeches, still rustling in their leaves, and above them rose a hill.

"Carn Pentyrch," said Cilmin, nodding at it. "Another Iron Age hillfort, but not half as good as Tre'r Ceiri."

It was a magical spot, soothing, peaceful, even secretive, with an aura of vast antiquity. Our goal, it turned out, was the ruins. To the left was a massive square structure built of huge irregular blocks. Inside was a basin some ten feet square and a couple of feet deep, surrounded by steps and rough stone benches. It was full of water which gently welled up at the back and overflowed through a drain in front.

"Meet St Cybi," said Cilmin, introducing us. "He was a Cornishman, a century before old Beuno. And this is his well. There's no way of telling how old the building is. But the water was supposed to be healing, and in the eighteenth century they added this cottage" -- he gestured at the adjoining ruin -- "for the custodian to live in, and to house the people who came here for the cure."

"What did it cure?"

"Lameness, fever, blindness. I don't think any of those applies to you."

Except blindness, just possibly, if I over-used my right hand.

"But do you have any warts?" he asked. "It cures them too."

"Well, actually I do. Two of them. What do I do? Drink the water?"

I could hardly believe it would work, but anything for a giggle.

"No, just rub it on. Hang on, I'll fish some up for you."

Someone had left a plastic bottle behind. He stepped down to the pool, filled it, climbed up again and sat on a bench. My warts were in an interesting place, and to get at them I would have to partly undress. Oh well. I was not bashful, nor was I averse to putting a little temptation his way. It would be interesting to see how he reacted. He might even anoint me himself. So I stood in front of him, my middle quite close to his head. I undid my belt, unzipped my flies, and lowered my trousers. One wart, which was rather a nuisance, was under the waistband of my boxers, which I pulled down further than was strictly necessary. But he was not going to anoint me.

"Hold out your hand."

He poured water into it, and I rubbed it vigorously on, wetting my boxers.

"God, it's cold!"

Cilmin only smiled. To ring the changes, I yanked up the left leg of the boxers, which not only exposed the second wart high on my thigh but emphasised my package. He poured me another handful and I applied that too. But he was watching with an interest that was no more than clinical.

Damn.

I rapidly resumed my trousers before the package grew too big.

"How long does it take to work?"

"Oh, a few weeks at most."

Over dinner it emerged that in ten days' time Goronwy and Priscilla were off on a cruise to the Caribbean in search, as they put it, of a bit of warmth.

"But you're not going?" I asked Cilmin, alarmed, and surprised at the strength of my alarm.

"No. I can't, what with college. Half term only lasts a week, and they'll be away for three. And somebody has to be here to exercise Rasmus. And, above all, I'm the world's worst sailor. Whenever we've crossed to Dun Laoghaire I've been seasick. Three times now."

"Four times, dear."

Discussion of the cruise and the Caribbean saw us through the meal. It left me puzzled.

"I like your parents, Cilmin," I said over the washing up. "In fact I'm envious. My Mum's OK, if you deal with her right, but I sometimes wish I had a father. A good father."

"You never see him, then?"

"He's dead. And they were divorced soon after I was born."

I was not ready to let that gross skeleton out of the cupboard. Not yet.

"But there's something I don't understand," I went on. "Do you mind me asking? What does your father do?"

"Nothing. Or not much that pays. He's director of a company or two. But we live off investments, and off the meagre rents of the farms we own. He's an anachronism. He lives in the past, or tries to. He's a JP. He's been High Sheriff. He's chairman of this county society and president of that. He votes Tory, he's in favour of our troops in Iraq, he's pro-hunting. He's everything I'm not. And his priorities are weird. If he wants a bit of warmth, he splashes out on a Caribbean cruise rather than spending it on central heating. Mum's of the same mind. I love them, but they drive me mad."

Lovable, yes, however traditionalist. And on Monday morning they brushed aside my thanks for the weekend with a pressing invitation to come again, and actually thanked me for coming. They made it sound much more than a polite formula. Why? What I had done for them? But as I saw them glance at Cilmin, standing beside me as cheerful as I had seen him, I began to wonder. Did they think I had done something for him?

In the car, as we drove to Pwllheli I tried to thank him too, for his companionship, for showing me the sights, for the hospitality of his family home. That reminded me . . .

"Cilmin, another thing I don't understand. How Welsh are you? And your parents?"

"Utterly. Yet barely. We're a contradiction. I'm not surprised you don't understand. We speak Welsh like natives. We are natives. But we never speak Welsh among ourselves, or with our county neighbours. We've been anglicised so long. The first William Glynne married an illegitimate daughter of Henry VII and became serjeant-at-arms to Henry VIII. OK, the Tudors were Welsh, sort of, and that William would still count as a proper Welshman. But in the Civil War another William married the daughter of Cromwell's governor of North Wales, who was emphatically not a Welshman. It wasn't a very wise move either, seeing that most of our neighbours were Royalists. But ever since, like all the old families, we've been getting more and more anglicised. English public schools. English universities. English soldiers and MPs. But curiously, for the most part, marrying our neighbours -- Mum's an Edwards of Nanhoron. We're getting more and more inbred."

There was something there that did not quite add up.

"Why didn't you go to public school, then?"

That seemed to catch Cilmin unawares.

"Well, I did go to prep school," he said defensively. "In Llandudno, as a boarder. But when I was thirteen and should have gone on to Harrow, I decided I'd be, um, better off in a state school. That's all there was to it."

His tone discouraged probing. Oh well. Back to the original thread.

"But where do your sympathies lie? I mean, do you feel Welsh, or English?"

"Neither, really. I've never lived in England. I'm floating in a sort of vacuum, to be honest. And at the same time I feel trapped in a time-warp. It doesn't help that I'm doing history, I suppose. Or literature and music, come to that -- even there I gravitate by nature to the older stuff. Though you're dragging me up to date with Robert Hunter. But do you realise that pretty well everything I've shown you this weekend comes from the past? From the dolmen to the church. Even Lleuar itself. Wales is a dangerous place, in that way. At least rural Wales is. There's a nostalgia about it. It's anchored in the past."

"I know. But don't we need some sort of anchor?"

"Yes, I suppose we do, in moderation. But an anchor also stops us moving. I'm a contradiction too. I've a love-hate relationship with the past. And with Wales. I want to get out of Wales. Out of this time-warp. I always have wanted to."

Odd again. If he had always wanted to get out of Wales, why turn down the English public school that was lined up for him?

"But I can't get out," he went on. "Not yet. But till I do, I don't know what I am, Welsh or English or whatever. Any more than I know what I am in . . . in any other sense."

He was driving more slowly than usual and frowning in obvious pain. I had to offer him comfort, and went further than I ordinarily would.

"Well, I know what you are to me. A damn good friend. And we agree on so much. I know exactly what you mean about that nostalgia. That melancholy. I feel it too, here in Wales. I didn't in Scotland. Maybe I was too young then. But things are just as old up there, yet it's bustling and go-ahead and you can see a future. At least in Edinburgh."

He was interested. "Lucky you. And I envy you doing science, you know. That's for the present and the future, not the past. Do you feel Scottish still?"

"Oh yes. Certainly not Welsh, or English. Maybe British, a bit. And European too. But what I want to be is -- sorry, I know it sounds corny -- a citizen of the world."

"What are you aiming for in life, then?"

I thought very hard. "Fulfilment," I said at last. "Fulfilment in work. Fulfilment in my, er, personal life. What about you?"

"The same. I want both. Of course I do. But I can't see a prospect of either."

Cilmin's voice was infinitely sad.

Built to last till time itself

Falls tumbling from the wall,

Built to last till sunshine fails

And darkness moves on all,

Built to last while years roll past

Like cloudscapes in the sky,

Show me something built to last

Or something built to try.

Built to Last, 1990

There was much to think about, that week. The ice of my self-imposed solitude was breaking. Like a seal long trapped below, I could now begin to poke my head up through the cracks and look around. Consorting with Kenneth seemed to have done me no public harm. He introduced me to Megan and I liked her. I still wore my hoodie, the hood now usually down but ready to go up. Caution, rather than total withdrawal, was my new watchword. It was not much, but it was a start. And I knew who was responsible for it.

And I knew him better now. Not well, but better. In him were visible many of the standard features of the adolescent, and I had no problem with them. Unabashed earthiness, which I was coming to envy -- could I even coach myself to emulate it? Frivolity, which I longed to share. A degree of discontent, which I already shared. And opportunism, which amused me -- I had not missed how he flaunted his body. At the same time he revealed a quite unexpected depth, an unusual sensitivity, and an obvious honesty. My qualms had been unfounded. He was surely a rarity for his age. I had met nobody like him. And I already needed him as I had never needed anyone before.

On the other side of the coin, he too had his needs, and they were not the same as mine. What he had seen of me, I felt, he approved and understood. But would he understand what he had not yet seen? There had been some near misses. Some of his shots had been perilously close to the mark, and I had barely dodged them. Yet at last I had met a travelling companion. We had started off together, and started well. He seemed as happy to walk along with me as I was to walk with him. How far could we travel down the same road? Only time would tell.

But another stage of the journey was already in prospect. On Tuesday, Kenneth invited me to his place for next weekend.

"You're sure it won't cause any problems?"

"No, if you're your usual polite self. Mum's already quite intrigued about you."

I wondered what he had told her. As expected, my parents readily agreed, and on Friday afternoon I drove him home to his box in Maes Gerddi. He showed me the spare room, which was poky, and his own, which was bigger than I imagined, untidy, bright with Grateful Dead posters, and very much Kenneth. From the windows he pointed out the lie of the land and told me his vision of a flooded future.

"I see what you mean. When that happens,

Dim byd ond mawnog a'i boncyffion brau,

Dau glogwyn, a dwy chwarel wedi cau."

"Boncyffion?"

"Stumps."

"Oh, right. 'There's nothing but bog and brittle stumps, two crags, and a pair of quarries both closed down.' Yes, that's spot on. Who wrote it?"

"T. H. Parry-Williams. It's from a poem about Llyn y Gadair, up near Rhyd ddu. Your Welsh isn't bad, Kenneth, you know."

"Well, I've been learning it for five years. It gets me by. But it's still very much a second language. It always will be . . . Cilmin, want to see more of what I love and hate about this place?"

He took me down the High Street, past a succession of pubs and fish-and-chip shops and gift shops and charity shops and, near the end, the Edinburgh Woollen Mills shop. After crossing the river, we climbed to the top of a rocky tump which looked out across the sea and down the shadowy coast to where Harlech castle pricked the yellowing sky. Below us was the terminus of the narrow-gauge railway, built to bring slate from the quarries but now a Mecca for tourists. Beyond lay the quays, where the slate had once been stacked but now there sprouted a fungal growth of jerry-built holiday homes. Alongside was the harbour, created for the schooners which had carried the slate to the ends of the earth, but now a marina a-bob with expensive pleasure boats.

"Commercialised leisure," said Kenneth, "paying lip-service to the past. There's no long-term future in it. Come the next depression, it'll be gone. Now look to the left."

There was the Cob, the mile-long embankment which dammed the estuary, dwindling neatly to the far shore like a lesson in perspective.

"One day that'll be breached. With global warming, it's inevitable. Now look inland."

In the foreground were the sluices that let the river out but kept the sea from coming in. Beyond, the drab pastures of the reclaimed estuary receded flatly into the distance. Over them towered the presiding majesty of the mountains, layered in successive shades of blue-grey -- Ralltwen dark and Moel Ddu darkish on the left, Cnicht and the Moelwyn mid-toned to the right, and between them, remotely pale, the flanks of Snowdon.

"This was all water once," Kenneth said, "five miles of it, till a couple of the centuries ago when they built the Cob. I was reading a book about it the other day which quoted Thomas Love Peacock -- you know, the novelist. He was devastated when they drained it. I memorised what he wrote: 'The mountain-frame remains unchanged, unchangeable; but the liquid mirror it enclosed is gone.' Unchangeable, yes. And when the Cob breaks, it'll be a liquid mirror again. That'll put man back in his place. That's real permanence."

He turned to me.

"Cilmin, remember we were talking last Monday in the car, about history? I've been thinking about that a lot, these last few days. I can see the danger of getting anchored to the past. But don't we need a continuity, not just from the past, but into the future? A stability, to set our rickety little lives against? Maybe we'll make our own wee contributions, you and me, but we won't significantly change history. Any more than man will significantly change the universe."

"Agreed," I said. "Man's a blink of the eye in geological time. An amoeba in the universe."